Lessons learned managing GitHub Actions and Firecracker

Alex shares lessons from building a managed service for GitHub Actions with Firecracker.

Over the past few months, we've launched over 20,000 VMs for customers and have handled over 60,000 webhook messages from the GitHub API. We've learned a lot from every customer PoC and from our own usage in OpenFaaS.

First of all - what is it we're offering? And how is it different to managed runners and the self-hosted runner that GitHub offers?

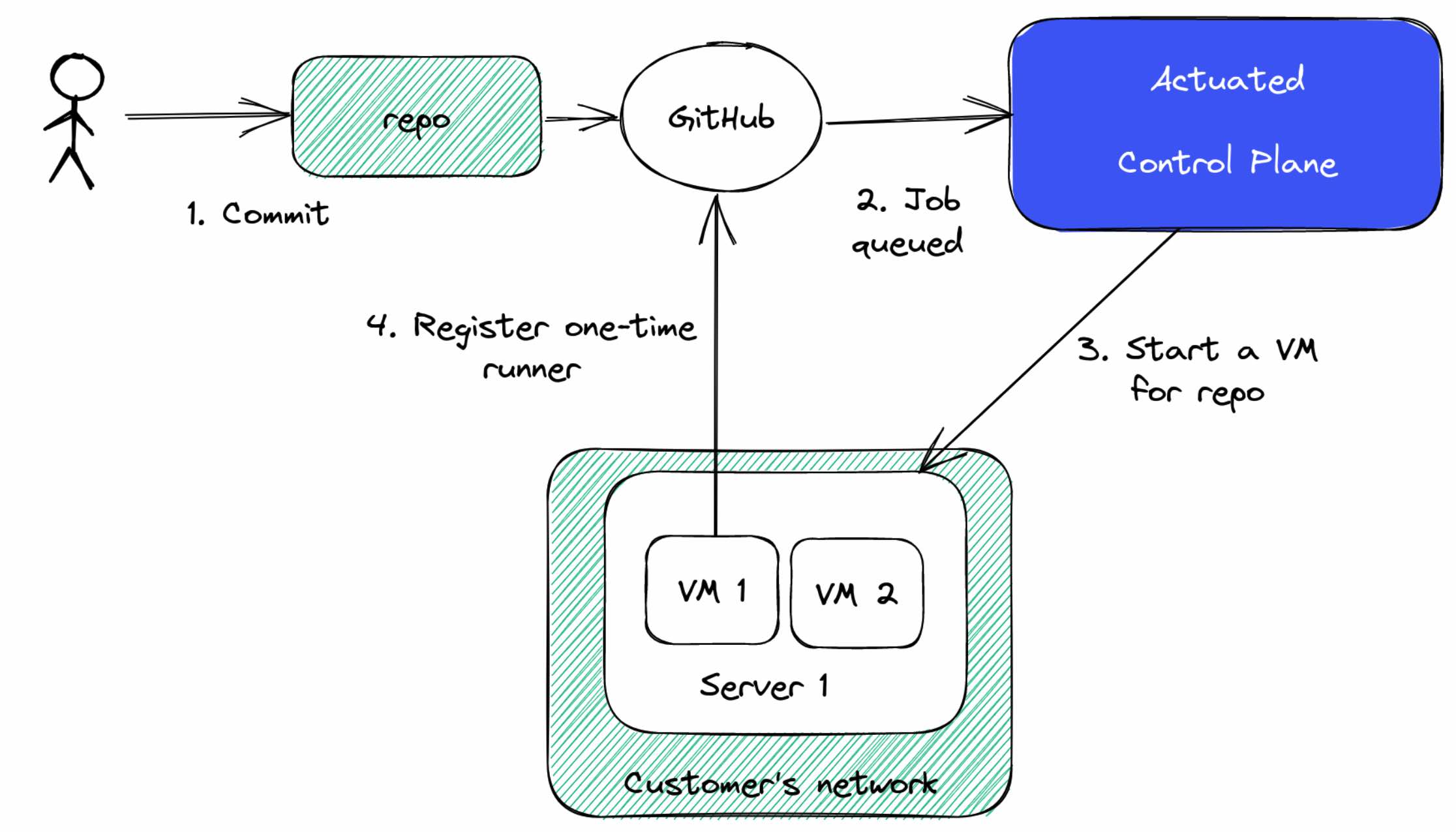

Actuated replicates the hosted experience you get from paying for hosted runners, and brings it to hardware under your own control. That could be a bare-metal Arm server, or a regular Intel/AMD cloud VM that has nested virtualisation enabled.

Just like managed runners - every time actuated starts up a runner, it's within a single-tenant virtual machine (VM), with an immutable filesystem.

Asahi Linux running on my lab of two M1 Mac Minis - used for building the Arm64 base images and Kernels.

Can't you just use a self-hosted runner on a VM? Yes, of course you can. But it's actually more nuanced than that. The self-hosted runner isn't safe for OSS or public repos. And whether you run it directly on the host, or in Kubernetes - it's subject to side-effects, poor isolation, malware and in some cases uses very high privileges that could result in taking over a host completely.

You can learn more in the actuated announcement and FAQ.

how does it work?

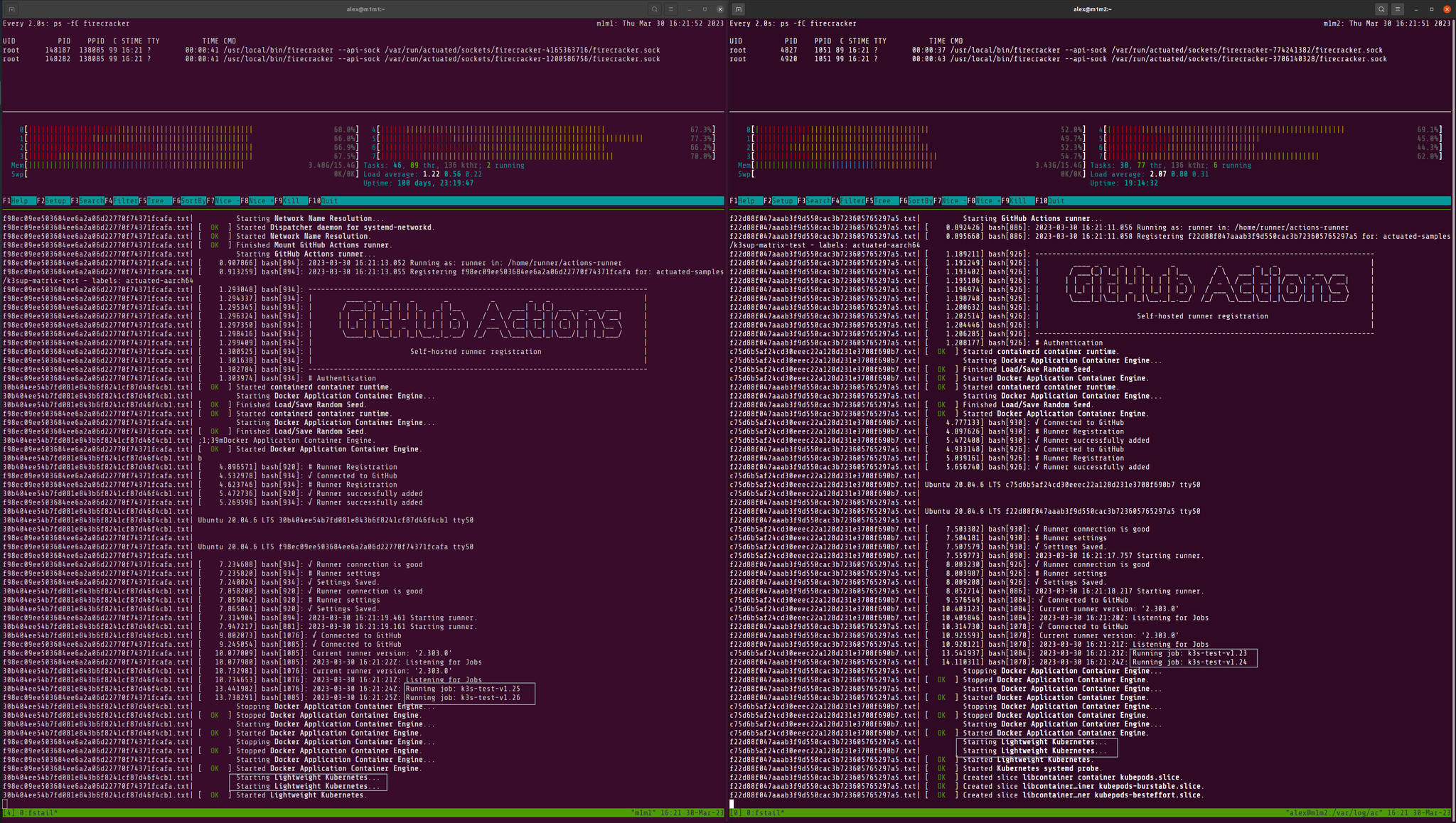

We run a SaaS - a managed control-plane which is installed onto your organisation as a GitHub App. At that point, we'll receive webhooks about jobs in a queued state.

As you can see in the diagram above, when a webhook is received, and we determine it's for your organisation, we'll schedule a Firecracker MicroVM on one of your servers.

We have no access to your code or build secrets. We just obtain a registration token and send the runner a bit of metadata. Then we get out the way and let the self-hosted runner do its thing - in an isolated Kernel, with an immutable filesystem and its own Docker daemon.

Onboarding doesn't take very long - you can use your own servers or get them from a cloud provider. We've got a detailed guide, but can also recommend an option on a discovery call.

Want to learn more about how Firecracker compares to VMs and containers? Watch my webinar on YouTube

Lesson 1 - GitHub's images are big and beautiful

The first thing we noticed when building our actuated VM images was that the GitHub ones are huge.

And if you've ever tried to find out how they're built, or hoped to find a nice little Dockerfile, you can may be disappointed. The images for Linux, Windows and MacOS are built through a set of bespoke scripts, and are hard to adapt for your own use.

Don't get me wrong. The scripts are very clever and they work well. GitHub have been tuning these runner images for years, and they cover a variety of different use-cases.

The first challenge for actuated before launching a pilot was getting enough of the most common packages installed through a Dockerfile. Most of our own internal software is built with Docker, so we can get by with quite a spartan environment.

We also had to adapt the sample Kernel configuration provided by the Firecracker team so that it could launch Docker and so it had everything it required to launch Kubernetes.

Two M1 Mac Minis running Asahi Linux and four separate versions of K3s

So by following the 80/20 principle, and focusing on the most common use-cases, we were able to launch quite quickly and cover 80% of the use-cases.

I don't know if you realised, things like Node.js are pre-installed in the environment, but many Node developers also add the "setup-node" action which guess what? Downloads and installs Node.js again. The same is true for many other languages and tools. We do ship Node.js and Python in the image, but the chances are that we could probably remove them at some point.

With one of our earliest pilots, a customer wanted to use a terraform action. It failed and I felt a bit embarrassed by the reason. We were missing unzip in our images.

The cure? Go and add unzip to the Dockerfile, and hit publish on our builder repository. In 3 minutes the problem was solved.

But GitHub Actions is also incredibly versatile and it means even if something is missing, we don't necessary have to publish a new image for you to continue your work. Just add a step to your workflow to install the missing package.

- name: Add unzip

run: sudo apt-get install -qy unzip

With every customer pilot we've done, there's tended to be one or two packages like this that they expected to see. For another customer it was "libpq". As a rule, if something is available in the hosted runner, we'll strongly consider adding it to ours.

Lesson 2 - It’s not GitHub, it can’t be GitHub. It was GitHub

Since actuated is a control-plane, a SaaS, a full-service - supported product, we are always asking first - is it us? Is it our code? Is it our infrastructure? Is it our network? Is it our hardware?

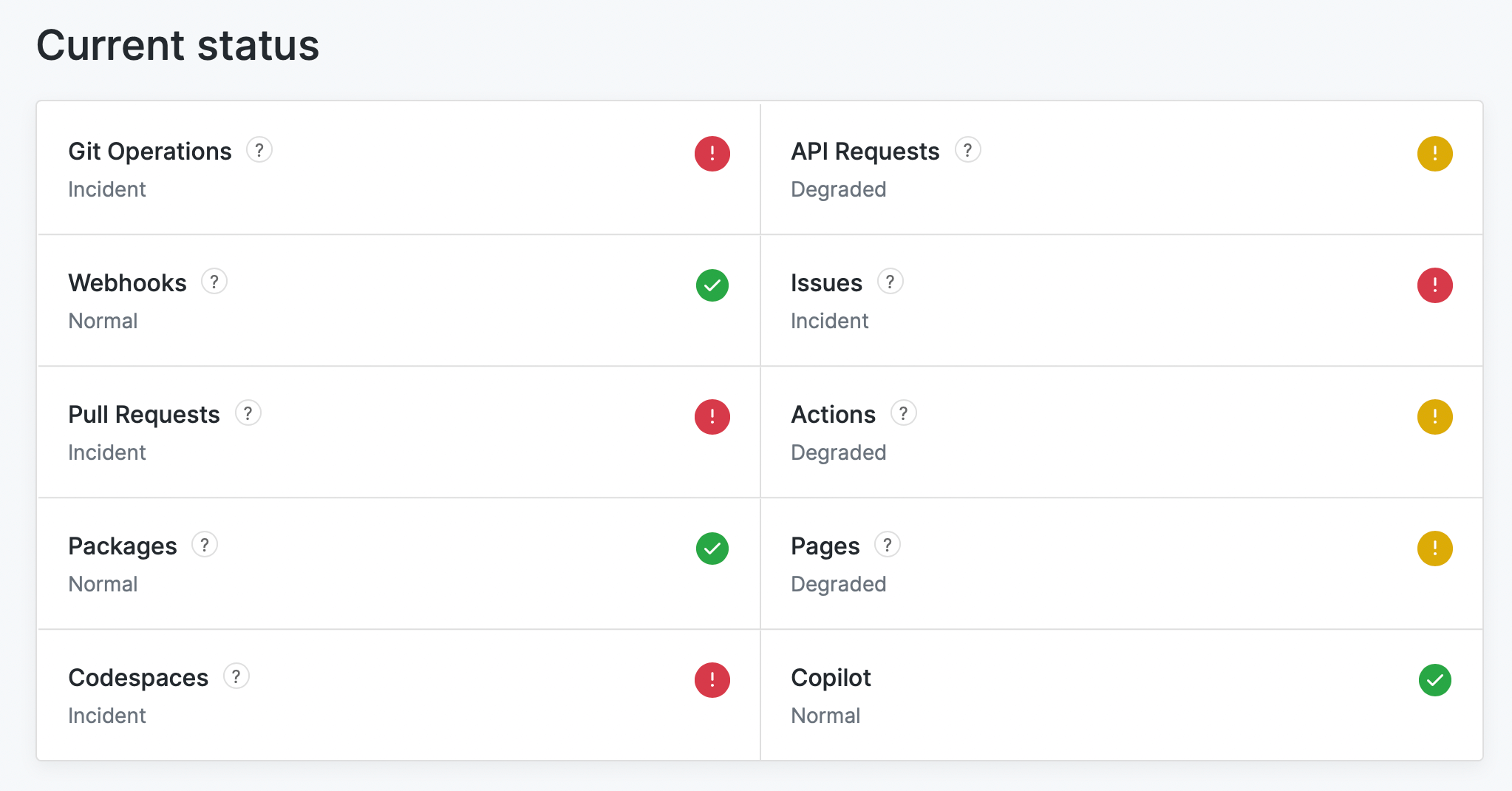

If you open up the GitHub status page, you'll notice an outage almost every week - at times on consecutive days, or every few days on GitHub Actions or a service that affects them indirectly - like the package registry, Pages or Pull Requests.

The second outage this week that unfortunately affected actuated customers.

I'm not bashing on GitHub here, we're paying a high R&D cost to build on their platform. We want them to do well.

But this is getting embarrassing. On a recent call, a customer told us: "it's not your solution, it looks great for us, it's the reliability of GitHub, we're worried about adopting it"

What can you say to that? I can't tell them that their concerns are misplaced, because they're not.

I reached out to Martin Woodward - Director of DevRel at GitHub. He told me that "leadership are taking this very seriously. We're doing better than we were 12 months ago."

GitHub is too big to fail. Let's hope they smooth out these bumps.

Lesson 3 - Webhooks can be unreliable

There's no good API to collect this historical data at the moment but we do have an open-source tool (self-actuated/actions-usage) we give to customers to get a summary of their builds before they start out with us.

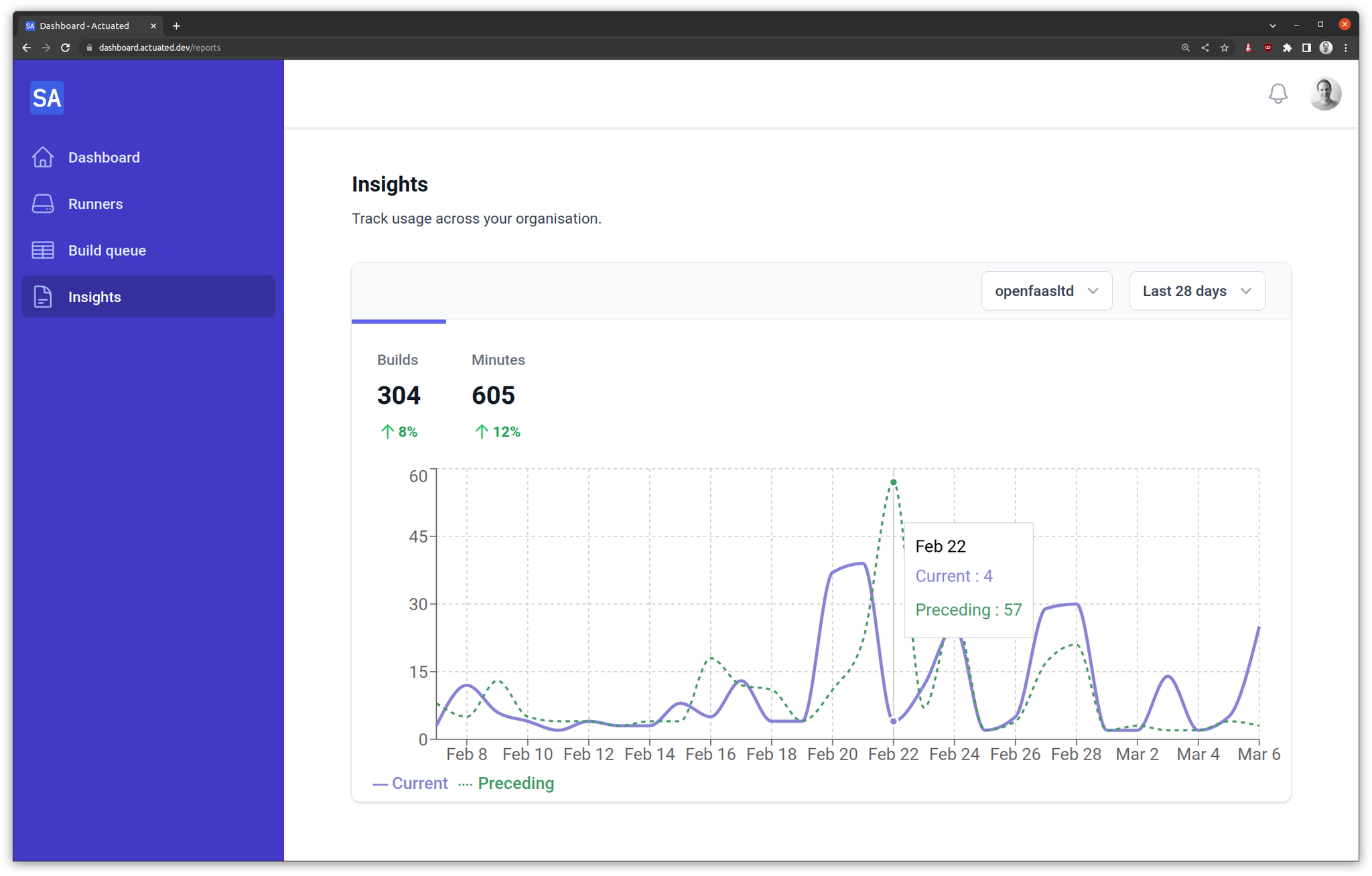

So we mirror a summary of job events from GitHub into our database, so that we can show customers trends in behaviour, and identify hot-spots on specific repos - long build times, or spikes in failure rates.

Insights chart from the actuated dashboard

We noticed that from time to time, jobs would show in our database as "queued" or "in_progress" and we couldn't work out why. A VM had been scheduled, the job had run, and completed.

In some circumstances, GitHub forgot to send us an In Progress event, or they never sent us a queued event.

Or they sent us queued, in progress, then completed, but in the reverse order.

It took us longer than I'm comfortable with to track down this issue, but we've now adapted our API to handle these edge-cases.

Some deeper digging showed that people have also had issues with Stripe webhooks coming out of order. We saw this issue only very recently, after handling 60k webhooks - so perhaps it was a change in the system being used at GitHub?

Lesson 4 - Autoscaling is hard and the API is sometimes wrong

We launch a VM on your servers for every time we receive a queued event. But we have no good way of saying that a particular VM can only run for a certain job.

If there were five jobs queued up, then GitHub would send us five queued events, and we'd launch five VMs. But if the first job was cancelled, we'd still have all of those VMs running.

Why? Why can't we delete the 5th?

Because there is no determinism. It'd be a great improvement for user experience if we could tell GitHub's API - "great, we see you queued build X, it must run on a runner with label Y". But we can't do that today.

So we developed a "reaper" - a background task that tracks launched VMs and can delete them after a period of inactivity. We did have an initial issue where GitHub was taking over a minute to send a job to a ready runner, which we fixed by increasing the idle timeout value. Right now it's working really well.

There is still one remaining quirk where GitHub's API reports that an active runner where a job is running as idle. This happens surprisingly often - but it's not a big deal, the VM deletion call gets rejected by the GitHub API.

Lesson 5 - We can launch in under one second, but what about GitHub?

The way we have things tuned today, the delay from you hitting commit in GitHub, to the job executing is similar to that of hosted runners. But sometimes, GitHub lags a little - especially during an outage or when they're under heavy load.

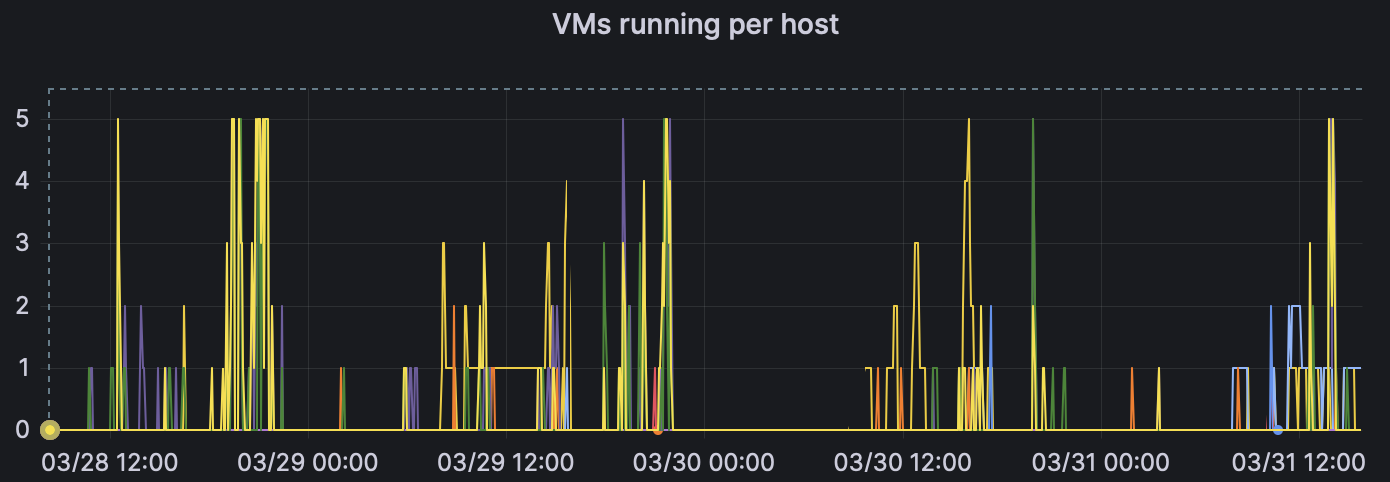

Grafana Cloud showing a gauge of microVMs per managed host

There could be a delay between when you commit, and when GitHub delivers the "queued" webhook.

Scoring and placing a VM on your servers is very quick, then the boot time of the microVM is generally less than 1 second including starting up a dedicated Docker daemon inside the VM.

Then the runner has to run a configuration script to register itself on the API

Finally, the runner connects to a queue, and GitHub has to send it a payload to start the job.

On those last two steps - we see a high success rate, but occasionally, GitHub's API will fail on either of those two operations. We receive an alert via Grafana Cloud and Discord - then investigate. In the worst case, we re-queue via our API the job and the new VM will pick up the pending job.

Want to watch a demo?

Lesson 6 - Sometimes we need to debug a runner

When I announced actuated, I heard a lot of people asking for CircleCI's debug experience, so I built something similar and it's proved to be really useful for us in building actuated.

Only yesterday, Ivan Subotic from Dasch Swiss messaged me and said:

"How cool!!! you don’t know how many hours I have lost on GitHub Actions without this."

Recently there were two cases where we needed to debug a runner with an SSH shell.

The first was for a machine on Hetzner, where the Docker Daemon was unable to pull images due to a DNS failure. I added steps to print out /etc/resolv.conf and that would be my first port of call. Debugging is great, but it's slow, if an extra step in the workflow can help us diagnose the problem, it's worth it.

In the end, it took me about a day and a half to work out that Hetzner was blocking outgoing traffic on port 53 to Google and Cloudflare. What was worse - was that it was an intermittent problem.

When we did other customer PoCs on Hetzner, we did not run into this issue. I even launched a "cloud" VM in the same region and performed a couple of nslookups - they worked as expected for me.

So I developed a custom GitHub Action to unblock the customer:

steps:

- uses: self-actuated/hetzner-dns-action@v1

Was this environmental issue with Hetzner our responsibility? Arguably not, but our customers pay us to provide a "like managed" solution, and we are currently able to help them be successful.

In the second case, Ivan needed to launch headless Chrome, and was using one of the many setup-X actions from the marketplace.

I opened a debug session on one of our own runners, then worked backwards:

curl -sLS -O https://dl.google.com/linux/direct/google-chrome-stable_current_amd64.deb

dpkg -i ./google-chrome-stable_current_amd64.deb

This reported that some packages were missing, I got which packages by running apt-get --fix-missing --no-recommends and provided an example of how to add them.

jobs:

chrome:

name: chrome

runs-on: actuated

steps:

- name: Add extra packages for Chrome

run: |

sudo apt install -qyyy --no-install-recommends adwaita-icon-theme fontconfig fontconfig-config fonts-liberation gtk-update-icon-cache hicolor-icon-theme humanity-icon-theme libatk-bridge2.0-0 libatk1.0-0 libatk1.0-data libatspi2.0-0 ...

- uses: browser-actions/setup-chrome@v1

- run: chrome --version

We could also add these to the base image by editing the Dockerfile that we maintain.

Lesson 7 - Docker Hub Rate Limits are a pain

Docker Hub rate limits are more of a pain on self-hosted runners than they are on GitHub's own runners.

I ran into this problem whilst trying to rebuild around 20 OpenFaaS Pro repositories to upgrade a base image. So after a very short period of time, all code ground to a halt and every build failed.

GitHub has a deal to pay Docker Inc so that you don't run into rate limits. At time of writing, you'll find a valid Docker Hub credential in the $HOME/.docker/config.json file on any hosted runner.

Actuated customers would need to login at the top of every one of their builds that used Docker, and create an organisation-level secret with a pull token from the Docker Hub.

We found a way to automate this, and speed up subsequent jobs by caching images directly on the customer's server.

All they need to add to their builds is:

- uses: self-actuated/hub-mirror@master

Wrapping up

I hope that you've enjoyed hearing a bit about our journey so far. With every new pilot customer we learn something new, and improve the offering.

Whilst there was a significant amount of very technical work at the beginning of actuated, most of our time now is spent on customer support, education, and improving the onboarding experience.

If you'd like to know how actuated compares to hosted runners or managing the self-hosted runner on your own, we'd encourage checking out the blog and FAQ.

Are your builds slowing the team down? Do you need better organisation-level insights and reporting? Or do you need Arm support? Are you frustrated with managing self-hosted runners?